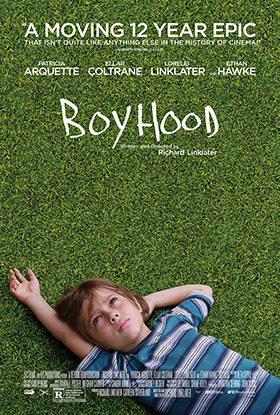

I recently went to the movies with my childhood friend Joanne to see Boyhood. Filmed over 12 years, director Richard Linklater caught on film the magic and misery of growing up.

We meet the main character, Mason, as a six-year-old boy lying on the grass, staring up into the blue sky. And we watch as he morphs into a shaggy-haired 10-year-old on a dirt bike, a troubled 13-year-old hating his alcoholic stepfather, and later a thoughtful, if not a bit pompous, 18-year-old going off to college.

Played by the same actor, Ellar Coltrane, covering 12 years of his well, boyhood, this feat in modern filmmaking leaves us inexplicably attached to him. Not much happens in the movie, but we root for him. We want him to figure himself out. We want him to have a good life.

Today, as I honor the 12-year anniversary of my mother's death, part of me wishes I could watch a film of my life over the past dozen years. Sounds narcissistic, I know. But I think it would help me realize how much I've grown.

Sometimes it's hard to remember that. Like on Sunday night, when the anticipation of the anniversary coming and the pain of missing my mom squeezed my heart so tight I couldn't sleep. On that night I felt like a little girl—the 17-year-old who found out her mom had cancer, the 20-year-old whose mom died.

But a part of me fought it. You're 32, I thought, you're too fucking old for this.

I'm tired of it hurting.

I'm tired of it continuing to hurt.

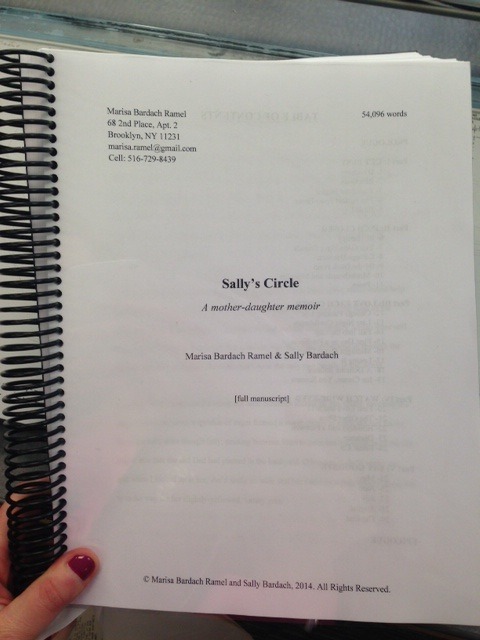

This year carries a particular weight. Although it feels amazing to have finished writing the memoir my mom and I began co-writing when she was sick, I feel heartsick for not being able to share it with her. I find myself telling her over and over again, while pedaling on the elliptical, while walking in the sunshine down the street, before I go to sleep at night: I finished it, Mom. I finished our book. I fucking finished it. (She didn't really mind cursing.)

Friends, and friends' moms, and my mother-in-law, and my very sweet readers have been telling me that I should continue blogging. That people will find comfort in seeing how far I've come and that things get better. But on nights when I feel my heart pinch with pain, I doubt myself. What do I have to offer? How much has really changed?

After a fitful sleep on Sunday night, I woke up on Monday morning and headed to the gym. I pedaled as fast as I could on the elliptical and thought about my mom. I thought about how I want things to be different. That I want to be more accepting of her death. I know that is the final piece that is missing.

Walking home from the gym, a Muse song I loved in college blasting on my headphones, I spotted a guy I knew from college who had recently moved to my neighborhood. He was even wearing a backpack. It was as if I was transported back to the Syracuse University quad.

And yet. So much has changed. I live in Brooklyn. I'm a working writer. I'm married, about to celebrate my two-year anniversary. I have more gray hair than black. A few days earlier I'd spent the day at the beach with my college roommate—and her two-year-old daughter.

I feel 32. But in a good way.

I am no longer that grieving girl, even if she rears her ugly head every once in a while. She will always be a part of me, the same way my mom will always be a part of me. We can't let go of who we are. But we can hold on with all our might to who we've become and the happiness we've found. And that's what I intend to do.